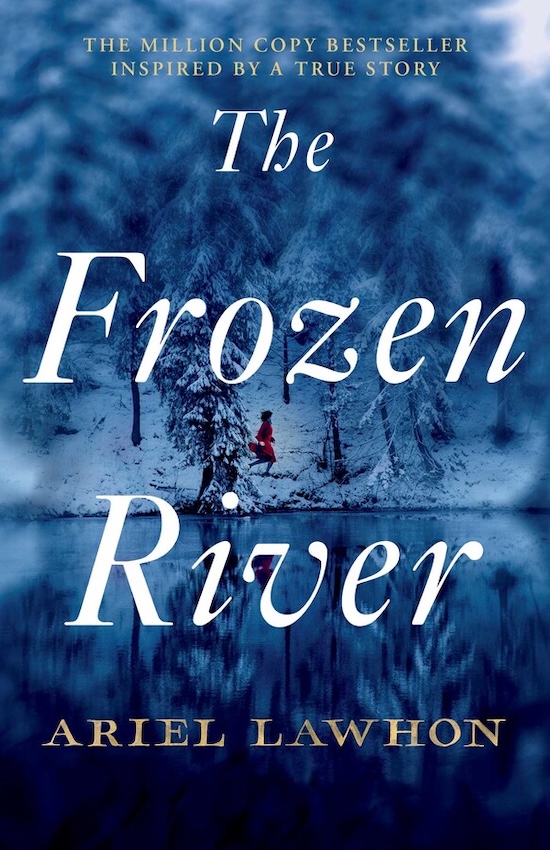

There’s something about settings in winter that can be very atmospheric. Ariel Lawson conjures up the depth of a very cold winter in The Frozen River, set in Maine in the late 1700s. Mere decades before, the militia had a fought long and hard to drive out the French as well as the native people of the area, ready for settlement. Martha Ballard, our protagonist, lives in the town of Hollowell with her family, her husband running a sawmill on the river, Martha the town midwife.

The story begins when Martha, with her medical expertise, is asked to examine a dead man, pulled from the river just before it ices over completely. As soon as she sets eyes on him, she is shocked to see that it is Joshua Burgess, one of two men accused of raping Rebecca Foster, her friend and the wife of a pastor. Rebecca had upset some townsfolk by making connections with the local Wabanaki people. What is also disturbing is that Joshua has been beaten and hanged.

When a newly-graduated doctor arrives and declares that the injuries sustained by the dead man are consistent with drowning, Martha is appalled to see her opinion discredited. She decides to find out what really happened, particularly when she learns that her son had an altercation with Joshua at the town dance on the night in question. She’s also determined to find justice for her friend Rebecca, who is still emotionally and physically scarred by her ordeal.

I keep up with the journals because I enjoy it, but also because it is my job. One of the duties of my profession. As a midwife and healer, I am witness to the details of my neighbors’ private lives, along with their fears and secrets, and – when appropriate – I record them for safekeeping. Memory is a wicked thing that warps and twists. But paper and ink receive the truth without emotion, and they read it back without partiality. That, I believe, is why so few women are taught to read and write. God only knows what they would do with the power of pen and ink at their disposal. I am not God – nor do I desire to be – but, being privy to much of what goes on behind closed doors in this town, I have a rather good idea what secrets might be recorded, then later revealed if more women took up the pen.

The plot really sweeps you along for the first half of the book and I couldn’t put it down. And then it kind of stalled. It was still interesting, in that the book is peppered with Martha’s diary entries, based on journals the real Martha Ballard kept, and you get a lot of the day-to-day life of a midwife in winter. The saddling up – she has a horrifically scary stallion called Brutus she’s still getting used to – and riding out in all weathers to tend to women in labour.

Apparently Martha never lost a mother during childbirth and her skills are recorded here, as well as those of a French speaking Black woman known as Doctor, who visits from time to time. But women skilled in medicine were not taken particularly seriously, and Martha often has a battle on her hands to make her patients and their husbands see sense. She’s a feisty character, always knows best, and a thorn in the side of powerful men. We also get a lot of her relationship with her husband Ephraim, still an intense passion now they’re in their fifties.

Then there are Matha’s battles against the local judge and businessman, Joseph North, the other man accused in the rape of her friend. He’s a nasty piece of work, and has the power to make things difficult for the Ballards. The ending is quite the showdown, if a little difficult for this reader to swallow. The author has written quite a lengthy explanation in a note at the end of the book about her reasoning here and the research which informed her story.

I’m glad I read The Frozen River as I had known little about this corner of history and the life of this interesting woman. I can see why the author wanted to fill in so much detail of her history, family and the settler township where she lived. I feel a more carefully edited version would have made a better novel. Overall it’s an engaging read and a three-star read from me.