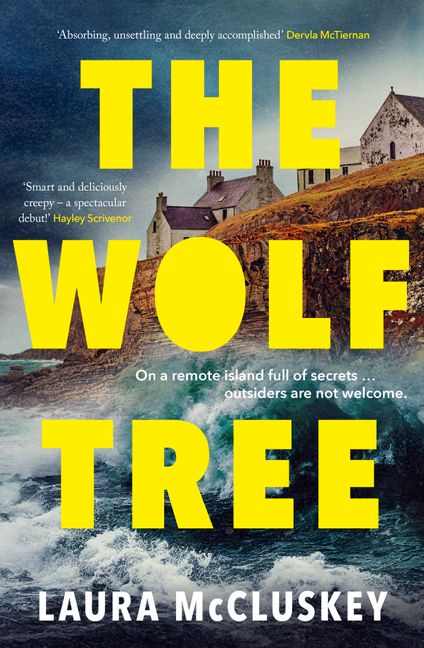

When I spotted on Netgalley a second book in Laura McCluskey’s DI Georgina Lennox series, I quickly expressed my interest. I’d been well entertained by George’s first appearance in The Wolf Tree, a crime novel set on a remote Scottish Island, full of secrecy, superstition and twists. George is a stroppy character, young for a DI but has a good nose for detective work. So she’s partnered with DI Richard Stewart, an experienced avuncular sort, the good cop to George’s bad, doing his best to keep George out of trouble.

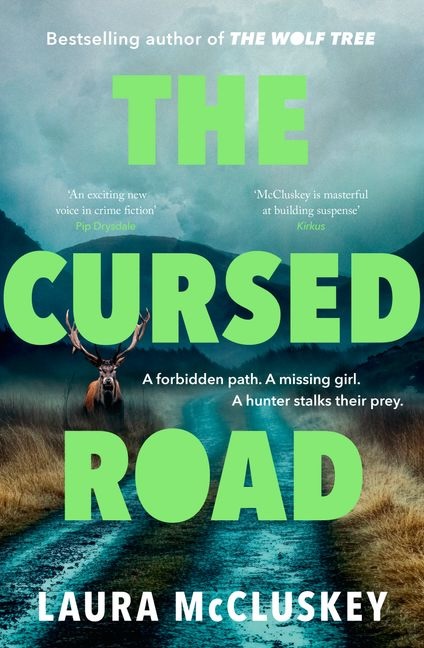

But in The Cursed Road, the tables have been turned. The traumatic events of the first book left both cops reeling, George undergoing some months of recovery and therapy, which have made her stronger, steadier. Richie on the other hand has not done the therapy, won’t look George in the eye, and has a short fuse that has their Superintendent worried. When a case comes up – the discovery of the body of a young woman in a remote corner of the Highlands – the two are sent to the town of Kirkcree to investigate, George also tasked with keeping an eye on Richie, reporting back anything that causes concern.

Emotions are running high for Richie. He’s the lead because ten years ago, a young woman disappeared from the same area. Cara Reid had a difficult start to life, lacked family support, but she always kept in touch with her younger brother, until suddenly she didn’t. Richie has never forgotten the case, blaming himself for not finding her. The new victim was found with Cara’s name scratched on her arm. The two cases must be linked, surely.

It takes less than six hours for the press to start calling her Bambi.

The moniker is as cruel as it is inaccurate; in the story, Bambi survives. What they really should have called this woman, her body found in a remote area of the Scottish Highlands just before dawn this morning, is ‘Bambi’s Mother’ – especially after the pathologist dug out the bullet, a .270 Winchester, from between her third and fourth ribs.

‘A perfect shot,’ one local police constable was quoted admitting, ‘if you thought you were bringing down a deer.’

But just as effective in bringing down a person, George thinks as she thumbs through the article on her phone.

George and Richie settle in somewhat testily at their small-town inn, supposedly there for just one night to see what they can find out from interviewing the pathologist and investigating the crime scene. It would be easy to see this as a shooting accident gone wrong. Further along the road where the body was found is an exclusive resort catering to international tourists wanting to hunt deer. Investigations unearth disputes the owners have with an old Scottish family that has lived in the area for centuries in their crumbling castle. Suddenly the story is peppered with interesting characters and potential suspects.

Other people on George’s radar include the creepy guy who eyeballs George at the village pub, and the journalist Hendry Shaw who made a big story out of George and Richie’s discoveries on the island. He particularly highlighted George’s part in the case, which hasn’t helped her relationship with Richie. George doesn’t hesitate to give Hendry a piece of her mind, especially when he follows them to Kirkcree. But is he beginning to wear George down?

A curse, a hundreds-year-old feud and a ghostly apparition all add to the atmosphere in this curious case. Clues and suspicious behaviour stretch the stay of the two detectives and with that the danger level rises. The detective’s partnership is put under pressure and George has to be the mature one, adding a bit of depth to the characterisation. The story builds nicely in pace with a nail-biting finish and George shows her mettle. It all adds to a clever, original and entertaining murder-thriller and a four-and-a-half-star read from me.

The Cursed Road was published this week on 24 February. I received a review copy courtesy of Netgalley and Harper Collins Publishers Australia.