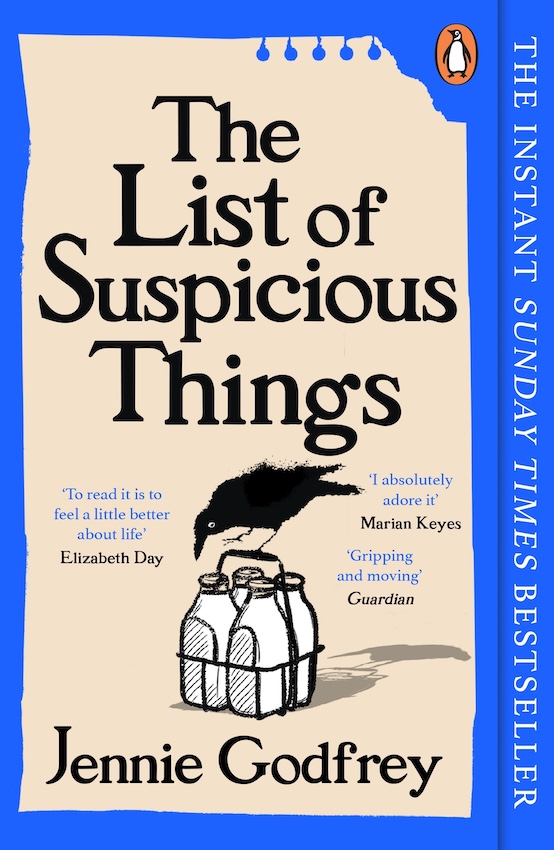

The List of Suspicious Things is a debut novel which takes you back to 1979. Thatcher has just been elected PM and the Yorkshire Ripper is at large, killing young women, while the police have few clues to his identity. In Miv’s Yorkshire town the mills have closed down, so things are already tough, and likely to get tougher. At home, Miv’s mother never speaks, Auntie Jean delivers food to the table and terse comments, while her dad seems a bit lost.

When the family thinks a move down south might be a good idea, Miv is desperate. At twelve, she’s bright but a bit socially gauche, partly due to her home life, so her friendship with Sharon is too precious to lose. She’ll do anything to save it so decides to investigate and catch the Yorkshire Ripper. She buys a notebook and makes lists, and with Sharon’s help, begins to look for suspicious characters close to home.

As names are added to the list, the reader is introduced to the people of the town, beginning with Mr Bashir who runs the corner shop. He’s one of the nicest adults Miv knows but he has dark eyes and a moustache, so makes the list. There’s a truck driver from her father’s work, people she knows from church and a teacher among others. Other people in the community include Helen at the library – because where else do you go for information in 1979?

The people we saw on our way to school were like the buildings we passed: predictable and unchanging. At eight-fifteen we chimed, ‘Morning!’ in perfect unison to Mrs Pearson, out walking her snappy Jack Russell. After her, we knew we would say hello and stop for a chat with the man in the corner shop, as he would be outside by now, arranging the daily newspaper stand. He would call us the ‘Terrible Twosome’ and we would laugh, as if it were the first time he had said it.

Just before we got there, Sharon nudged me hard in the ribs and muttered, ‘Watch out!’ under her breath. Following her gaze, I saw another familiar person, the only person we didn’t say hello to on our journey and whose name we somehow knew was Brian, though we didn’t use it. To us, he was just ‘the man in the overalls’.

Of course, the girls don’t catch the Ripper, but their investigations uncover some of the darker elements going on in the town – the racism, the misogyny, the prejudice against those who are a bit different. Miv learns one or two secrets that are a bit close to home, and finds herself caught up in some of the fallout. She’s a girl who is left too much to her own devices, there’s just too much going on at home for consistent parenting. But then in 1979, kids were often left to find their own entertainment and the town is their playground.

Through Miv you also see the struggles of the adults in the story. Sometimes the narrative shifts to Austin, Miv’s dad; Helen; or Mr Bashir, who each have personal sadness and secrets. The setting – the late ’70s is well realised. Mr Bashir is always singing along to his favourite Elton John songs, jeans go from bellbottoms to stovepipes and Sharon buys a glittery lipgloss to try. And it’s also very Yorkshire, though not posh Yorkshire – the kids go ‘laiking about’ and at least one character’s house has an outdoor loo.

While overall I enjoyed the book, I did feel at times that it was rather overloaded with issues. So many dark things happen with a lot to fall on Miv’s small shoulders. Still, The List of Suspicious Things is a quirky and interesting novel, easy to get lost in. I was reminded of Joanna Cannon’s The Trouble with Goats and Sheep – another novel about two young girls investigating – in this case a neighbour’s disappearance – also set in the ’70s, and which is well worth checking out. The List of Suspicious Things is a three-star read from me.