Well, yes I know this book is about a lot more than its setting. There’s a man’s lingering grief for his late wife. A family of elderly women and a secret they never got to grips with from World War II. There’s some parent-child dynamics and a potential love affair. And all of it comes together in a captivating story that maybe takes a little while to get going, but once you get in, has you nicely hooked.

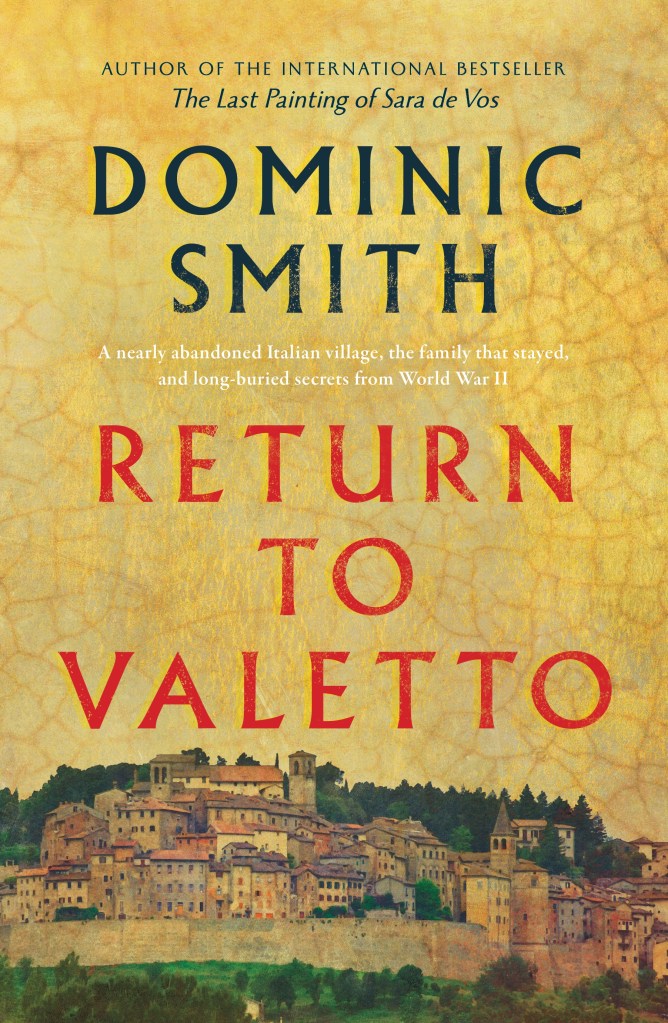

But when I look back on this book in months and maybe even years to come, I know it will be the setting that I’ll think about first. Valetto is Dominic Smith’s invented town in Umbria, which sits on a pedestal of volcanic rock. Much of the old town has fallen down into surrounding valleys, a 1971 earthquake urging many of its inhabitants to relocate. It has become a kind turreted and terracotta island, connected to the surrounding landscape by a footbridge.

Hugh is an American historian who specialises in the study of abandoned towns – there’s hundreds of them dotted around Italy and what better place to begin than Valetto, the childhood home of his mother and where even today his grandmother and three aunts still live. The Serafino women, all widows, are a big chunk of the population which has dwindled to just 10. In a few weeks it is to be his grandmother’s 100th birthday and a party has been planned.

A spanner in the works is the woman who has taken possession of Hugh’s cottage on the Serafino property, supposedly given to her mother for services rendered when Hugh’s grandfather, Aldo, was a resistance fighter during the war. Elissa Tomassi is adamant that the cottage is legally hers, just as Hugh’s aunts are convinced she’s a squatter with no legal tenure. Hugh is sure there can be a way to keep everyone happy and is caught in the middle. But he has to get to the bottom of what happened during the war and discovers not one but two family mysteries to solve.

The past will take Hugh back to Elissa’s home town in the north of Italy to find out what Aldo did in the closing years of the war. He’ll also discover a link between his mother and the Elissa’s that is a trickier memory to unlock and will reveal a crime that has been swept under the carpet. The story builds to a powerful and moving conclusion that has you glued to the final chapters as past deeds are dealt with.

What could be done with the wreckage of the past? As a historian I’d always believed that studying the past could reveal hidden meanings and patterns, that motifs lurked in the underbrush, but now I saw the neap tide of history washing up flotsam on an empty beach.

I enjoyed Return to Valetto enormously, not only for the setting which seems to be a big part of every scene. The late autumn mist across the valley that comes and goes and adds even more mystery. The large old villa that is the Serafino home with its cavernous rooms and crumbling frescoes. There’s the old family restaurant established by his grandmother, where you can see abandoned place settings and dusty menus from a night in 1971. (Oh, did I forget to mention this books is also a hymn to Italian regional cuisine?)

And the characters are a joy. The three aunts, each with their own peculiar ways and at times difficult interactions with each other. I have a particular fondness for books about aunts, going back to P G Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster stories, and here Iris, Rose and Violet are brilliant. The grandmother with her iron determination to host an unforgettable birthday celebration with an ever-growing guest list and a despairing cook. Both Hugh and Elissa have daughters that make an appearance, so it’s an inter-generational tale as well.

I can’t help feeling Dominic Smith had a wonderful time researching and writing this book as his love for history, particularly social history, as well as all things Italian shines through. This is the second novel by this author I have read and recall that Bright and Distant Shores was one of my top reads for the year it came out. I’ve heard lots of good things about The Last Painting of Sarah de Vos as well. Return to Valetto gets the full five stars from me.

By the way, the fictional town of Valetto is inspired by Civita di Bagnoregio in Lazio – in case you want to visit, either in person or via the Internet.