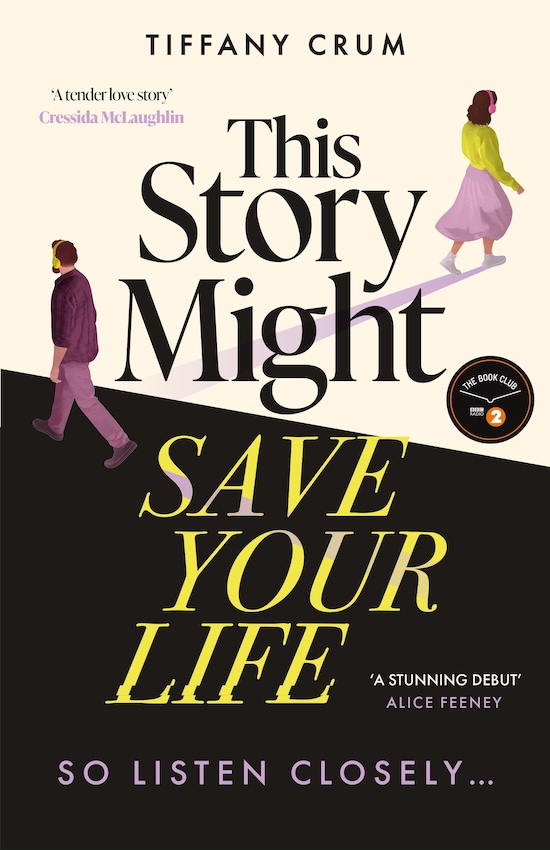

I hadn’t a clue what to expect from this debut novel, and even looking back having turned the last page, it still seems an interesting mix of genres – by turns a psychological thriller, a dramedy and a love story.

This Story Might Save Your Life is named after the massively successful podcast hosted by besties Benny and Joy. The idea behind the show is life-threatening situations, and how to survive them. Each episode describes one such event researched by one of the team, who then asks the other, how would you escape – for instance, being caught in the mouth of a humpback whale. So yes, we’re not just talking house fires and boats capsizing.

There’s a lot of comedic banter, and it’s really the personalities of the two that make the show work. Neither Benny or Joy ever thought they’d be still doing the show years later but subscribers write in with their own near-death survival situations and it goes from strength to strength. Joy’s husband Zander has helped grow the brand, running the business side of things and even taking the show on tour.

The situation is complicated by Joy’s medical condition. She has narcolepsy, which means those closest to her are aware that she might just fall asleep at any moment. With care and meds she leads a fairly normal life. The other complication, which happens right at the start of the book, is that during the season that the Santa Ana winds threaten trees and cause general mayhem, Joy and Zander disappear from their home.

We get Benny’s story about the disappearance, the police investigation and the growing concern that the two may be in danger. Benny’s not a big fan of Zander – there’s some jealousy there between them – so his main concern is for Joy whose narcolepsy makes everything tricky anyway. Interwoven with the all the CSI, the search teams and suspicious looks from a probing Detective Keller is Joy’s story. She and Benny have a publishing deal to write a two-person memoir, so this is her story, going back to her learning to deal with her illness, make a life for herself, her meeting Benny and then Zander.

The switching between the two stories makes you beaver through the chapters desperate to see what happens next. Joy’s backstory is just as interesting as Benny’s search for clues, slowly bringing us up-to-date with potential reasons for the disappearance. The plotting is excellent, but the characters are engaging too. Joy and Benny are charming and funny – Joy captures our empathy because she’s just so positive in spite of her medical condition, while Benny’s a bit of a goof, but also intense. He’s also been through some difficulties and has a temper.

Zander is a bit of a dark card, and there are other characters who have emotional connections to the two MCs – among them Zander’s sister Mallory, and Benny’s ex, Luna, which adds further complications. It’s quite likely someone’s lying, but who? And even Benny and Joy seem to be hiding something. So there are plenty of twists that keep you eagerly reading to the end. I also loved the L.A. setting which Tiffany Crum helps you visualise – a place I’d be happy to revisit.

I read this novel courtesy of Netgalley and Hachette, Australia for an honest review. It’s a great story, and I’d certainly be keen to read more by Tiffany Crum. This Story Might Save Your Life is due for publication on 10 March and is a four-and-a-half star read from me.