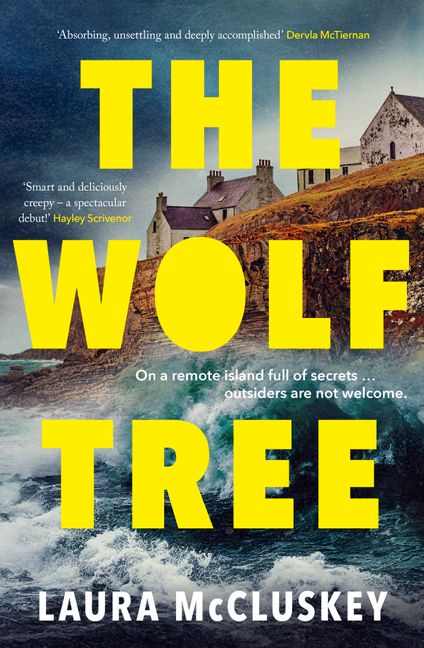

An island can provide just as much of a locked-room mystery as one in any building, particularly when it’s a remote island like Eilean Eadar, a wild and isolated spot off the West Coast of Scotland. In The Wolf Tree, we are in the shoes of DI Georgina (George) Lennox, who is just getting back to work after an attack that left her badly injured. This new case is supposed to be a box-ticking exercise, and she’s here along with her partner DI Richie Stewart to sign off on a probable suicide – a case to ease George back to work gently.

Of course, the reader knows that isn’t going to happen and things look problematic from the start. Even the boat crossing is wild and treacherous, the weather when they arrive, wet and freezing, the accommodation inconveniently at some distance from the little township. The two cops settle in, George doing her best to disguise from her older colleague and mentor her dependency on painkillers. The island has had to manage without a police presence, without a doctor, a school or social services of any kind for so long, so it isn’t surprising that the locals have learned to manage everything themselves. So they’re understandably reluctant to accept the interference of two cops from Glasgow.

Then there’s the case. Young Alan Ferguson, eighteen and busy applying for places at universities, had supposedly flung himself off the top of the island’s lighthouse. Alan was handsome and amiable, the only child of a widow, but she puts up a wall of animosity when George and Richie show up to ask questions. Hot on their tails, the priest arrives – a hearty, gregarious man, keen to help oil the wheels of the interview. The islanders, like Alan’s mother, are hostile towards mainlanders. It’s only the priest and the postmistress who are welcoming, or is that just nosiness?

People think that death by drowning would be peaceful. But if there is any truth to that, it’s a peace that comes after the worst thirty seconds of your life. And it’s a fate that, until today, George Lennox never considered might befall her.

With her jaw clenched against both the biting cold and sudden dips, George stands on the heaving deck of the police launch; constricted by the bulk of an orange life vest, a duffel bag over her shoulder. She clutches a leather briefcase in one hand, the slick railing with the other. The weather has changed dramatically in the last few hours. The soft white clouds that farewelled her on Skye have turned black and heavy, and the waves that claw at her feet are splintered iron, threatening to drag her down all twelve thousand feet to the sunless floor of the North Atlantic Ocean.

Wariness towards incomers goes way back – the islanders had seen off the Protestant Reformation which turned the other western isles and much of Scotland. But Eadar is still staunchly Catholic. Or is it? What is the strange design that adorns the lintels of many of the houses, and why is George warned not to go anywhere near the woods. Pagan beliefs, mythology and superstition seem to hover on the fringes of everyday life. Then there’s the sound of howling wolves that disturbs George at night in a place where surely no wolves exist.

At twenty-eight, George is young to be a Detective Inspector, so it’s easy to imagine in her a tenacity her partner, eager to get back home with his family, seems to lack. It’s this tenacity that sees George asking awkward questions that Richie has to smooth over to avoid unpleasant confrontations. What will she have to do to earn the locals trust enough to talk to her? And what of the three lighthouse keepers who disappeared a hundred years ago? Can this mystery possibly have a connection to the death of Alan Ferguson?

It’s hard to determine which is more hostile and dangerous, the weather on Eadar or the people who live there. By the time we get to the end of the book, there are some stunning revelations and some spookily atmospheric scenes. George, in spite of terrible headaches, manages to think on her feet and probe the truth out of people in a case that will shock the whole community and mainlanders alike. She upsets Richie again and again with her disregard for her personal safety, and this looks unlikely to change anytime soon.

A first of a series, The Wolf Tree is a suspenseful and entertaining read, promising more tricky investigations for our two very different DIs. The Cursed Road is due for publication early next year. I particularly enjoyed the audiobook version of The Wolf Tree, which was read by Kirsty Cox. It’s a four-star read from me.