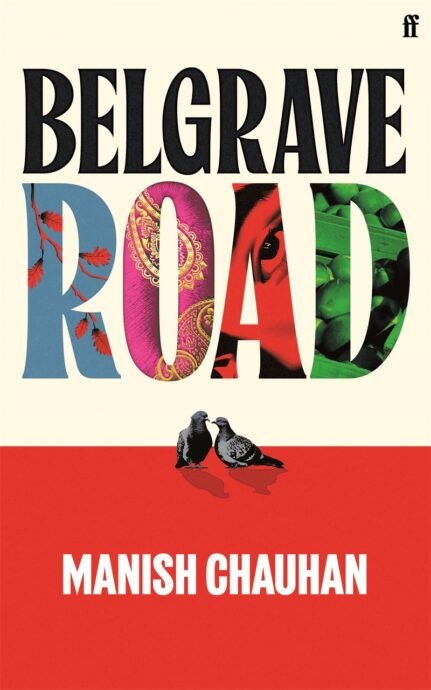

This debut novel describes the immigrant experience from two quite different points of view. It begins with Mira’s arrival from India to make a new life in Leicester with her husband. She’s twenty-three, and this is an arranged marriage. In itself this would be fascinating for a reader from a culture where arranged marriages, apart from those on reality TV, don’t really happen. What can it be like to suddenly share a bed, a home, a life with someone you hardly know? Mira has to remain married to Rajiv for five years to stay in England, if that’s what she wants. Somehow you get the feeling though, there’s no turning back – that she could never face returning home to India to be a disappointment to her parents.

Mira had hoped she could use her beauty therapy diploma to start her own business – she’s bright and ambitious – but beauty therapists are a dime a dozen in this part of Leicester, an area that is surprisingly full of Indian people, Indian shops, Indian food outlets. It could even be a lot like home, if only it wasn’t so cold. An opportunity arises for Mira to work in the kitchens of a sweet shop, where she makes friends with the other workers and where, across the yard, she first sees Tahliil.

Tahliil is a young man who has recently had a harrowing journey from Somalia with his sister and lives with his mother in a tiny flat. He’s not legally allowed to work, has not even registered as an asylum seeker when we first meet him, but picks up several part-time jobs, paid in cash, no questions asked. He’s diligent and well-mannered, so is kept on. It’s at the cash-and-carry where he shifts stock, sometimes delivering grocery items to the sweet shop next door, where he meets Mira.

Mira begins to question her marriage. Rajiv is older and has a history with a woman who secretly texts him, and friends he sees without Mira. So it’s easy to fall into a friendship, and then something more with Tahliil. The story includes Tahliil’s struggles as an asylum seeker, the lengthy wait for his paperwork to go through, the worry that he could be sent home. The fact that he’s Muslim means any relationship with Mira would be unacceptable to his family.

This is such a compelling novel, beautifully written, with its two very different characters, who find themselves in desperate situations. Perhaps an older version of themselves would think twice, but when you’re in your twenties it’s so easy to let your heart hold sway. And why wouldn’t they? They’ve both travelled so far. Why would they settle for anything less than a life lived on their own terms? As a reader you can’t help thinking of the roadblocks, and whether each has the fortitude for the journey ahead of them if they want to be together. This drives the story and keeps you engrossed to the end.

Other characters have their struggles too. Mira’s mother-in-law seems to be eternally optimistic rather than seeing the reality of what’s going on with her family, with her marriage. Rajiv’s cousin Rupal is in a same-sex relationship she’s completely committed to, but struggles to formalise before her family. Tahliil works for an old man who hardly ever sees his daughter, and is estranged from his son.

I found the setting of Leicester, with its huge immigrant population, quite fascinating, a place that must seem cold and physically inhospitable to those from warmer climates, and yet which offers opportunities and safety. Belgrave Road is a brilliant story, and Manish Chauhan really gets into the heads of his characters, making their lives believable. If you want to understand what makes people leave their country for new beginnings in the West and the struggles they face, this is well worth reading – a five-star read from me.

I read Belgrave Road courtesy of Netgalley and Faber & Faber (UK). The book is due for release on 29 January.